Nagaland: Kisoma + Kohima: PAPperlaPAPp

10. + 11. November 2025

II’m already writing a bit here about the Hornbill Festival. It takes place every year from December 1–10, and has been held since 2000. That means last year was its 25th anniversary. I still have no real idea whether the Nagas themselves think it’s absolutely fantastic on its own, or how important the spectators are. In any case, it’s big, and supposedly around 4,000–5,000 people usually come from abroad. It’s also very popular with Diamir – the trip was quickly fully booked, so they immediately added another one in reverse order. This arrangement works well: both groups can spend two days at the festival, and the local guide can greet the next group right after..

The preparations are already in full swing; a lot has to be rebuilt, improved, expanded, and so on. The grounds where it takes place aren’t far from Kohima and are called Kisama. So we drove there, allowing me to have a look around and know a bit more before the group arrives.

The grounds are much smaller than I expected. There is a kind of stadium with lots of seats, where performances take place in the middle. There was a lot of construction work going on.

Stadionpart

Stadionpart

And next to it, the community houses of the 16 Naga groups stretch up the hillside.

“village”

“village”

1

1

2

2

3

3

4

4I’m still not quite sure what to make of it after this visit. Maybe ‘suspicious’ is the word that best describes how I feel. A newspaper also published some criticism, saying that Kohima focuses too much on the Hornbill Festival in its tourism strategy and then has far too few tourists during the rest of the year.

The next day I rested a bit more again. My cold is still quite deep in my chest. And in the evening there was an event coming up! It was Remembrance Day at the best hotel in Kohima (though it actually wasn’t that fancy). Azo, the local contact, had a travel group of three Brits who were very keen to go, and he thought he might as well ask me if I wanted to join. And that was a good idea, because once again I ended up with plenty of food for thought….

I had already been to the war cemetery. And who exactly wanted to remember what here — and why? Up to now, I’d always had this equation in my head: British = colonisers = bad. I was surprised that they like travelling to their former colonies; I tend to assume that this must feel uncomfortable. These three told me quite cheerfully that they were following in the footsteps of their families, some of whom had lived in India in the past. And the people here welcomed them extremely warmly and enthusiastically, almost treating them like honoured guests.

stage

stage

I was curious and looked it up on my laptop. It seems to me that ChatGPT explained it very well, and I’m now putting it into my own words. Using my own phrasing helps me understand the connections better and notice where there are gaps or inconsistencies.

Nagaland and the Britishers

So: In Nagaland, the issue of British colonization is a bit more complicated and different. When the British arrived in this area (mainly around Kohima) from about 1830 onwards, they were considered enemies. They wanted to tax the Naga tribes, stop headhunting, and govern. There was fighting (which I will explain more in a later post about Khonoma), and the British essentially won. After that, they began to bring “order” to the region. Here, however, they proceeded much more skillfully and respectfully than in other parts of India.

They did not exploit the region through plantation agriculture or anything similar; they allowed the tribes to keep their village elders and a kind of semi-autonomy. There were British officials with an ethnological interest who saw the hill peoples as “noble savages” — and they allowed missionaries into the country. However, they also very quickly banned headhunting and inter-village warfare. The missionaries, too, were very skilled: they did not force Christianity on the Nagas but made it attractive and offered it. They built schools and introduced literacy and medicine. This was met with enthusiasm, and the moral outlook shifted very quickly by 180 degrees. Especially headhunting is often mentioned in conversations as something many now feel ashamed of.

During these years — that is, until at least the Second World War — things continued in a relatively friendly manner. The missionaries were very successful, the British were rather well liked (though of course not 100%, as they were still colonizers), and the Indians were rather unpopular. This intensified, among other reasons, when the Japanese advanced during WWII. They were supported by Subhas Chandra Bose, who wanted an independent India and thought he could achieve this better with the help of the Japanese. Nagaland was basically caught in between: not being a colony anymore sounded good, but was India really the better alternative? The Japanese, however, lost the support of the local people through violent actions. The British were not innocent either — but if you have to choose between two evils, you pick the one that is less cruel. And so the Nagas helped the British during the war, whether with infrastructure, food supplies, porter services, or even by fighting with weapons themselves.

When the British won the Battle of Kohima in 1944, they again acted shrewdly and honored many Nagas for their contributions during the war, funded scholarships for Naga children, and offered support in many ways — before they left the country in 1947. The fact that many of the missionaries came from the USA didn’t really matter; all Western Christians were generally viewed in a positive light.

The British guests were two sisters and the husband of one of them, who were following in the footsteps of their older relatives. One grandfather had been an engineer and, for example, built the hospital. Quite a few friendships had been formed back then — and so it no longer surprised me how warmly and enthusiastically the British women were welcomed here, and how positively they spoke about this place where their ancestors had spent a good time.

And that is exactly what is celebrated and remembered on Remembrance Day! The honour of those who fell in the war, and the friendly ties between the British and the Nagas.

singing

singing

In practice, it looked like this: Western songs were sung, many people received gifts, and then two gentlemen on stage began a conversation (all in English!). The topics were: a) that the role of the Nagas in the war has not found a very prominent place in the history books, and that they would like to change this in order to feel prouder of themselves, and b) stories that should also be told by the audience — because the people who still have direct memories are dying out.

The whole event was honoured by the presence of the Chief Minister. I had already seen him at the Lotha Hoho. This time he even shook my hand (he assumed I was also one of the friendly British visitors) and he was sitting right in front of me. He also shared some remembrance stories.

Mr. Rio

Mr. Rio

The audience was also encouraged to ask questions and contribute, and one woman actually brought up the topic of the PAP. She said that it was no longer so easy to invite foreign friends (apart from the British visitors and me, the only other Western face there was a lady from the Irish embassy in India).

The CM then gave an 11-minute speech (I recorded it, just to be safe), and it included the sentence that was most important to me: next week he would be in Delhi again to fight for a better solution — especially for the Hornbill Festival period. I really, really hope for that! The woman who had asked the question wasn’t a tour operator at all, but an engaged researcher on Nagaland. I practically begged everyone I met from the local travel companies to come up with a common strategy, at least for the festival, and then for all of them to stick to it. Of course very much in the sense of making entry easier. But also because you are simply stronger together than when everyone just thinks of individual solutions.

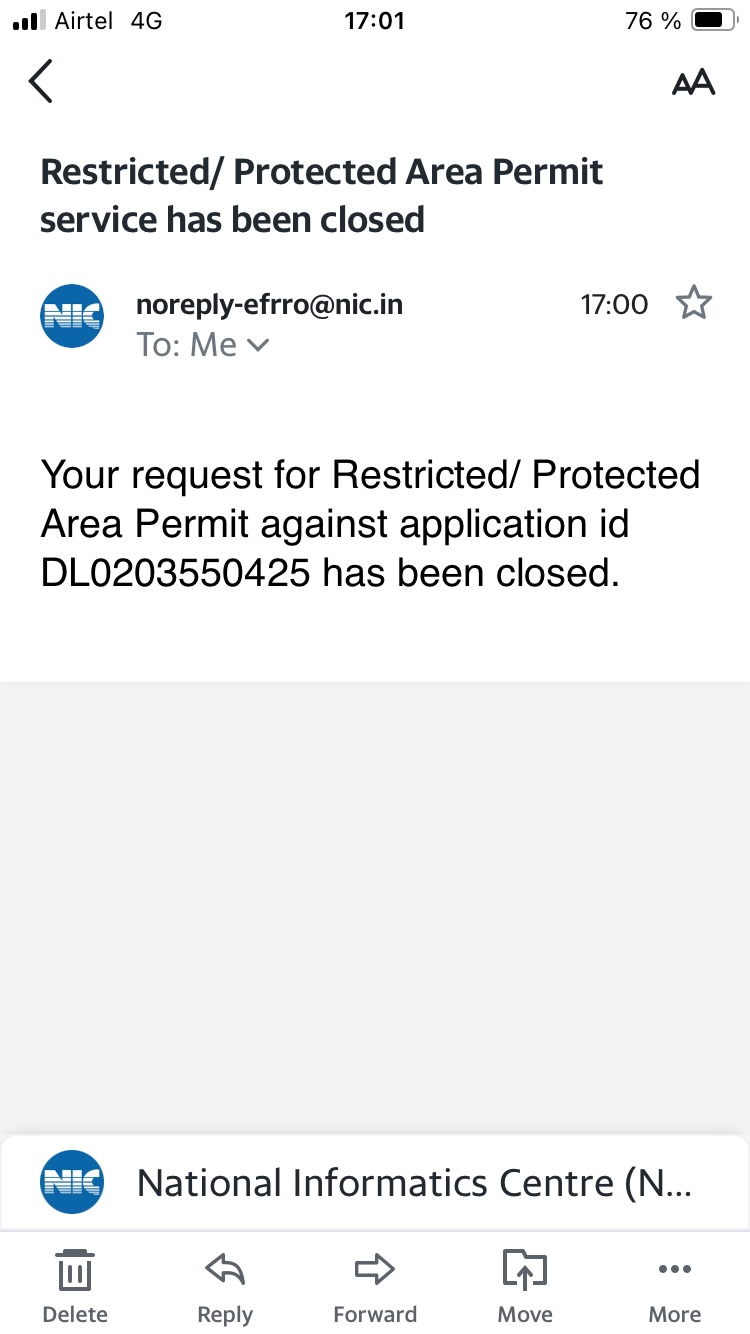

I’m jumping ahead a bit here in my own PAP story. The situation was that I was supposed to come to Delhi on the 11th, and I had written an email saying that I wouldn’t be able to make it. On the 12th, around 5:00 p.m., I then received the following emails:

Mail 1

Mail 1 Mail 2

Mail 2

So now I’m here more or less “illegally,” but I’m getting a second chance and no penalty. What I also think is this: if there really are 4,000 foreign tourists wanting to attend the Hornbill Festival, the authorities simply won’t be able to keep up with processing all the applications with the staff they have — even if all applications are submitted in good time.

In any case, we’ll just keep waiting for now, and I decided to stay here for another two days for certain activities, but then to leave Nagaland again for the time being.