Nagaland: Hornbill Festival – a pig donates itself

3. + 4. Dezember 2025

To reach the highlight of the trip, we still needed one more day of driving. In Dimapur we visited these ruins of the Kachari culture. By that point, all these different cultures had simply become too much for me in such a short time, so the visit was mostly limited to a sense of amazement at what interesting structures (around 100 of them) were scattered and standing around there. Their history is not really known either — what exactly they were used for, or what the place might once have looked like. Most of them were fenced off, but some could be entered — and then the reason for the fencing became immediately clear. Why do so many people feel the urge to immortalize themselves, or something else, everywhere?

1

1

2

2

3

3

You could tell that Christmas was approaching. More and more Christmas trees were being put up.

a special one

a special one

And then the time had finally come: a full day at the Hornbill Festival!

1

1

For ten days, daily shows of about two hours were presented in the arena, while in the huts next door the respective cultures were on display. On the one hand, the atmosphere seemed very friendly and cheerful to me; on the other hand, it didn’t excite me at all.

FPhotographie/Filming

I could have left my camera in my bag as well, but I felt silly coming home without any pictures. Others were snapping photos and filming like crazy—and that’s immediately one of my “points of criticism.” For many visitors, it seemed to be a purely visual spectacle, a chance to produce vast amounts of material for social media (there’s plenty of it online), home photo albums, or other collections. The main focus: exoticism. People in traditional dress posed and posed, smiling in selfie mode, and when they danced they were surrounded by a ring of raised cameras.

2

2

3

3

4

4

5

5

I asked the last gentleman here whether he really did this all day long and didn’t get tired. Yes, he said—one day it’s his turn, the next day it’s someone else. I usually smile too when I notice a camera pointed at me, and for certain purposes I can pose for longer periods of time, but not really for very long—at some point reluctance sets in. All the more impressive to me was the undiminished willingness of many to be photographed, even after hours.

I also found the visitors’ eagerness to take photos remarkable. But this difficulty—this sense of not quite understanding it—is something I’ve been carrying around with me for a long time:

- What do they want to do with pictures that countless others are taking as well?

- What do they want to do with pictures that rely purely on the visual appeal of the subject (like photos of sunsets—the sunset itself is impressive, but the photo of it is “no skill”)

And here is me during filming – taken by a local broadcast:

Screenshot

Screenshot

Exotic <=> Tradition

At the Hornbill Festival, 18 different Naga tribes were represented. Each had its own traditional clothing—the men’s outfits were far more elaborate than the women’s. On the one hand, that’s simply tradition, and I think it’s good that it hasn’t been completely relegated to the costume box. On the other hand, it conveys a strong sense of exoticism, because visually it is very far removed from everyday clothing. The colors and forms of the adornments were diverse and also magnificent to look at. What would actually have interested me was when these clothes are worn today outside the festival, what they mean to the people, how they feel about standing out so conspicuously, and what stories lie behind the individual details. I didn’t ask these questions—I didn’t know when, to whom, or how.

I think I have a fundamental unease with exoticism anyway. I haven’t yet found a good way of dealing with it for myself. I feel like what’s missing is conversation. Maybe I should make a more active effort to seek that out. And really, I could have asked how others feel about it. It obviously makes me speechless.

Here are some pic with exotic:

6

6

detail (the story behind it—really interested me. Maybe I’ll still manage to find out)

detail (the story behind it—really interested me. Maybe I’ll still manage to find out)

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

The footwear was also interesting and at times a bit amusing. I liked it when people wore flip-flops with socks. As the afternoon wore on, more and more of them changed clothes or left the festival—so there was gradually less exoticism to see. No wonder—it got quite chilly, and the clothing wasn’t really suited to the temperature.

In the evenings, there’s also an International Rock Festival in the arena. Critical voices find this very inappropriate.

Another topic regarding tradition: religion. Traditionally, they had a different faith, and now almost all were Christian. How do you celebrate that? There was a horn-blowing competition, and a seemingly very important man gave a speech. He said the Hornbill Festival had two main purposes: a) the communal gatherings and b) the honor of God. Then he asked the audience to repeat everything after him in unison. I was so annoyed that I didn’t have my camera on, and I found it extremely unsettling to see the exotically and traditionally dressed crowd chanting “Praise the Lord” and other church slogans in many voices.

This scene, for me, exemplifies my discomfort.

Encounters

It says: The Hornbill Festival was initiated in 2000 by the state of Nagaland to preserve the traditional cultural elements of the Naga tribes, promote inter-tribal encounters, and create tourism/income opportunities. For me, the inter-tribal encounters weren’t really visible—that would have meant differently traditionally dressed groups sitting together. But they stayed within their own groups. Perhaps it happened “behind the scenes.” Even the encounters between visitors and Nagas seemed, to me, to go little beyond photographs and exchanges of superficialities—though I can certainly count myself among those.

ChatGPT said:

Many days later, I realize that a) I either never want to go back there, or b) I would/should approach it very differently—namely, through other kinds of encounters and conversations. But that needs to settle in with me first. In the meantime, all I can do is observe my reactions—and they were such that I didn’t feel particularly comfortable.

Here are a few more impressions from the location:

17

17

18

18

19

19

20 (Nagaland is a dry state – except during Hornbill…)

20 (Nagaland is a dry state – except during Hornbill…)

21

21

Economy

The Hornbill Festival generates good income during those 10 days. Visitors sleep, eat, drink, travel, buy souvenirs—and some are organized through local travel agencies. (It reminds me of the Biathlon World Cup in my hometown, where a very large portion of tourist revenue is also concentrated in just one week.) During Hornbill, there are many opportunities to earn money—even the road between Kohima and the festival grounds is being rebuilt. But these are mostly short-term earnings, nothing that really helps people throughout the year.

ChatGPT said:

For Nagaland, the Hornbill Festival has by now become an enormous economic factor, while the organizers’ expenses are relatively low. Across India, there are very few festivals that generate so much local economic activity with so few visitors (for example, the Pushkar Fair requires significantly more visitors to achieve similar figures).

A conversation with ChatGPT about this whole topic is highly interesting, but it’s too much for me to reproduce here. For anyone who wants to know more, I can only recommend it—it really helps to clarify a lot of things for me.

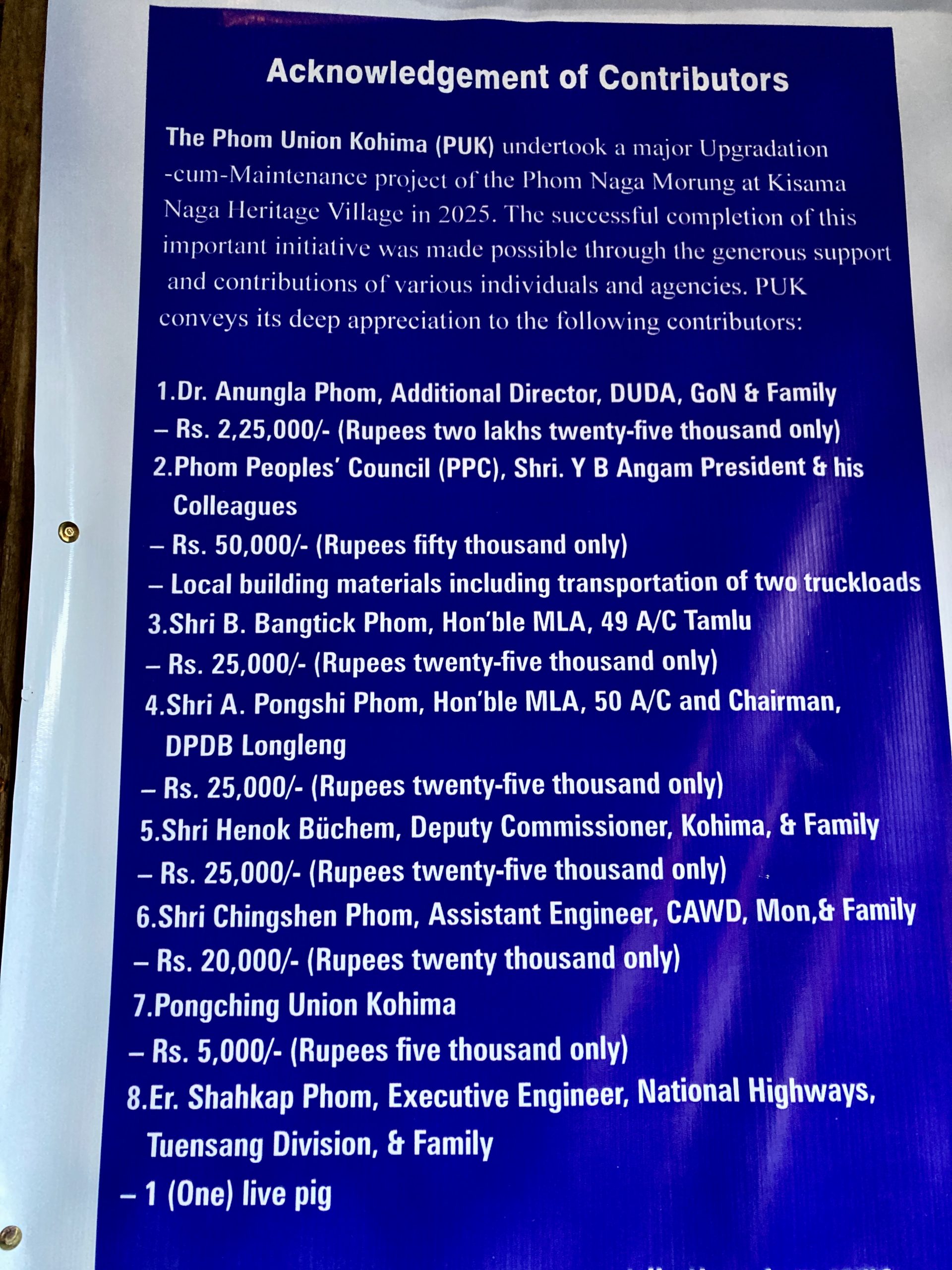

In one Naga group, I found this sign listing donors for the improvement of the morung. The most interesting of all was the last donor—the pig.

donation board

donation board

Is there a photo I took that I liked more than the others? Yes—and it’s this one:

Kiosk

Kiosk

Conclusion for me

I’m glad I went there to get my own impression. In principle, it largely matched what I had expected—except that I found everyone friendlier than anticipated. For me, it’s a good event for reflection and discussion, but not one that simply brings joy. ChatGPT is an excellent source of information—though it absolutely needs to be complemented by personal conversations. And: I process experiences better afterward than beforehand. I always need to have been somewhere first to develop more focused interest. Not ideal for a job as a tour leader.